Many people most closely associate Carnival with Mardi Gras or the weeklong celebrations in Rio, but this festival technically spans from Epiphany to Shrove Tuesday. For most church traditions, Epiphany falls on the day after Christmastide officially ends (January 5 is the Twelfth Day of Christmas) and commemorates the visit of the magi, Jesus’s baptism and the first miracle of Christ, which is kinda a lot.

This pre-Lenten period is marked with all of the excess that is held back during the 40 days preceding Easter. The name is said to come from a Latin phrase carne levare, which means to remove or say farewell to meat or flesh. Many adherents abstain from eating meat for the duration, but particularly on Fridays; the “flesh” translation is why many folks instead eat fish during this period. It’s worth pointing out that translating carne to “flesh” may also hint at the many more excesses of Carnival.

The technical length of Carnival varies because, while Christmas is fixed, Easter is changeable. The liturgical calendar does a lot of counting backward for important church occasions like Ash Wednesday. As such, Carnival may shrink or stretch, depending on when Lent falls.

But the length of Carnival celebrations varies by region and tradition for many reasons. First, many feel that celebrating Carnival during Epiphanytide – the days following Epiphany – is disrespectful. Complicating matters, the ending of Epiphanytide depends on the local or denominational tradition. For many, that period ends with Candlemas (also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ or the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, but which also marks another possible end of the Christmas season) on February 2nd; for others, Epiphanytide may stretch further. So while you may see pączki on store shelves already (hell yeah), most parades, feasts and festivals don’t happen until February is well underway. Too, the varying length of this period can make for some major celebratory burnout, so limiting the peak of revelry to a one-week window is generally in any city’s best interests.

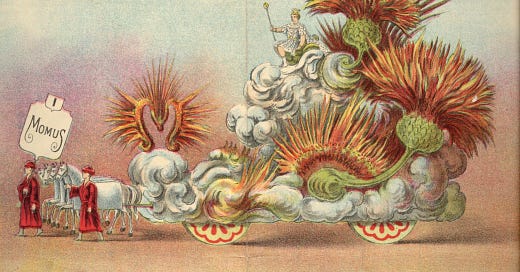

In Louisiana and other New World regions which hold Carnival festivities, the task is handled by local krewes, organizations dedicated to the planning of these parades and feasts. The term is thought to come from the Mistick Krewe of Comus, founded in 1856 in New Orleans, which holds tableau balls for members and guests (and also is, historically, suuuuper racist). The idea of secret members-only societies organizing Carnival festivities spread. Today, krewes generally organize their own celebrations anytime during the Carnival season and often also participate in larger citywide events, such as parades.

One of the most spectacular sights of Carnival are the parade floats, a point of pride for many krewes. Many scholars connect this tradition to the Roman Navigium Isidis, or ship of Isis; the goddess would be brought to shore in a wooden boat known as the carrus navalis to bless the start of the fishing season, and offering another possible origin of “Carnival.”

Historical aside: Churches in the middle ages would use parade wagons as moving backgrounds for passion plays, and they quickly became a staple of other moving celebrations. Carnival celebrants may have seen co-opting this Lenten tradition for their own revelry as a bit of sacrilicious fun. These parade fixtures became known as “floats” thanks to the barges of the Lord Mayor’s Show, but that’s a different blog post.