Hares have long been a popular icon in the theme of fertility. So prodigious was their reproduction cycle that some theorized that hares reproduced on their own, leading to an association between bunnies and the Virgin Mary (and other notable virgins) during the medieval period.

The Easter Bunny comes from German folklore. The exact time period in which he solidified as an egg-giving figure varies by source. We do know that a 1682 manuscript refers to a folk belief that the Easter Hare lays eggs for children to find; whether this was a common tradition is unclear.

“Mad as a March hare” comes from the bizarre antics that come with the March breeding season of the European hare; this makes them quite conspicuous during the Paschal season. To editorialize, I think it’s only natural that people would’ve invented folktales to explain the strange hops, chases and slaps of the bunnies in springtime.

The 19th century saw a surge in interest in Germanic folk traditions. Adolf Hotlzmann and Jacob Grimm used shaky research to connect Easter with the theoretical German goddess Ostara/Ēostre. They placed a hare in her hands and called that proof that she was certainly the root of Easter; they insisted she had bird companions, which explained away the eggs. (They were liars, but we just believe white men with pens, I guess.)

Around that time, the Pennsylvania Dutch helped popularize the Osterhase/Oschter Haws in the United States. If they were well-behaved, children would find colorful eggs in their caps or handmade nests around Easter.

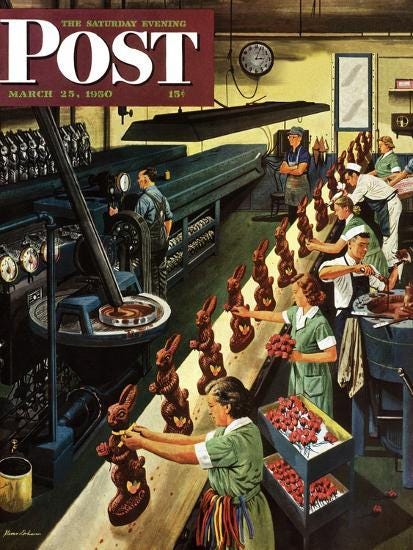

That’s a long introduction to how we got chocolate Easter bunnies, but it’s all (somewhat?) relevant. We’re not sure when Germans created rabbit molds for their confections, but we do know that German immigrants – and their offspring – popularized chocolate rabbits in the United States.

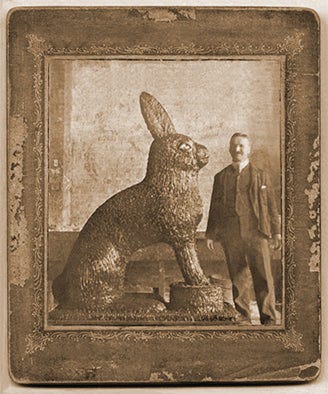

In 1890, Robert L. Strohecker wanted to draw business during the Easter season. To that end, he had a 5’ chocolate hare made for his storefront in Reading, Pennsylvania by the Luden’s company. (Yeah, the cough drops.) This move earned him the nickname the “Father of the Easter Bunny Business.”

Wait, wait, you guys have got to see this bunny:

Chocolate bunnies quickly became the showpiece of Easter baskets, with newspapers reporting the trend at the turn of the century. So why, oh why, are these big ol’ bunnies so… empty?

Having a 3-D bunny seems to have long been an important part of the equation; to this day, flat-backed bunnies are still seen as the inferior product, as there’s just no magic in that. But a solid 3-D bunny is decidedly difficult to eat. A Reese’s-filled bunny in my own household required a knife, so I can’t imagine trying to gnaw on a lump of chocolate that massive.

That lump of chocolate would also be expensive to produce – and buy. A secret of holiday candy is that each piece must tip a delicate balance between profits for the company and a customer’s willingness to pay for it. Specialty confectioners make filled bunnies, but the mass-produced bunnies are usually hollow and priced (more or less) accordingly.

Didja know? Chocolate bunnies were once banned in the US. During World War II, the War Production Board felt that stopping production on chocolate in shapes that were appealing to kids would help them abstain from sweets. Anything to help the troops! So on Easter 1944 and 1945, kids generally got bunnies in other forms, like carved wood figurines, soap and stuffed toys. While toys and trinkets were sometimes included in Easter hauls before the war, they became a huge part of the Easter tradition in the post-war Boom.